While they were perplexed about this, suddenly two men in dazzling clothes stood beside them. The women were terrified and bowed their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, “Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen. Luke 24:4-5

When he had said this, as they were watching, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight. While he was going and they were gazing up toward heaven, suddenly two men in white robes stood by them. They said, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven. Acts 1:9-11

Every few years a blockbuster film is released and we are inundated by the hysteria caused by it. Long before the release of the film, massive numbers of toys are released to stores and fast food restaurants and the rush to buy Star Wars “collectibles” is on. Today what we call “collectibles” used to be called “souvenirs.”

We human beings have a need to surround ourselves with reminders of where we have been and what we have done. We buy souvenirs, I think, to prove to ourselves and to others that we really were “there” and to impress on ourselves and on others the importance and meaning of the experience we had “then.”

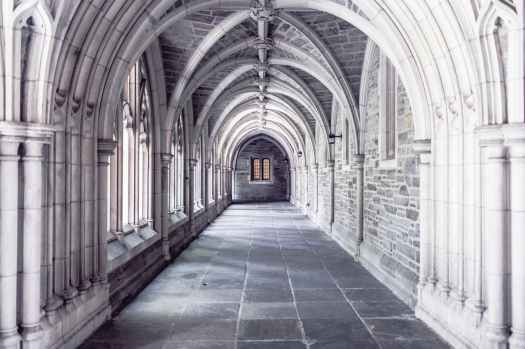

Often we do not fully experience an event because we are trying so hard to preserve it forever. We are trying so hard to remember it, that we forget it all the more easily. Here is an example from my own experience. At the defense of my dissertation at Duke University, Stanley Hauerwas, a professor on my dissertation committee, asked me to reflect on something Noam Chomsky had written. He read a long passage aloud quickly. I did not have a copy of what he was reading before me. While he was reading, I was trying to memorize what he was saying so that I could comment on it when he finished. I remember saying to myself as he read, “remember that, and remember that, and remember that….” When he finished, Dr. Hauerwas said to me: “What do you think about that assessment? I couldn’t remember a thing. I had tried so hard to preserve the memory, that I had remembered nothing. A friend of mine, who faced a similar encounter, a year or so later from the same professor, coolly asked if he could see and read the passage for himself. Why didn’t I think of that?

When the floor of Cameron Indoor Stadium, that fantastic arena in which many a great Duke Blue Devil basketball player has played, was replaced, fundraisers at Duke University were no fools. They sold off small pieces of the wooden floor to eager fans who wanted a piece of the place— more particularly a piece of the memories of what had happened in that place, and of all the people who may have played on that floor. Buyers now, for a fee, could hold a souvenir of basketball history in their own hands and own it.

Through the souvenir of a place or event, we hope to remind ourselves of who and where we were and to capture a piece of that experience forever. The living flowing blood that surged through our bodies when we experienced an event or a place first hand, is now in the object of the souvenir, a hardened piece of coagulated memory.

Early on Easter morning, a few women drawn from the group of Jesus’ disciples arrived at the tomb where Jesus had been hastily buried on the previous Friday just before the beginning of Passover. They had come at the first opportunity after the end of the Sabbath to anoint and prepare Jesus’ body for burial. Angels (literally “messengers”) of God ask them why they are looking amidst the past for Jesus. “He is not here, but has risen,” the angels remind the women.

After his crucifixion, the disciples fled Jerusalem, where their Lord had been crucified, and returned to the safety of the Galilean countryside. There they resumed fishing and their several occupations. At Jesus’ ascension into the heavens, the disciples are told to return to Jerusalem, a place of uncertain risk and danger, and to wait for their mutual empowerment by the Holy Spirit. Then they are to proclaim the good news of what God had done in Jesus to “the ends of the earth.”

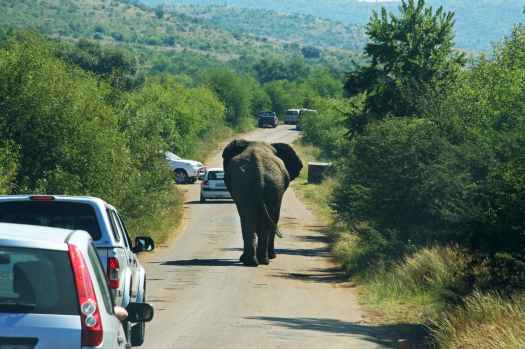

At the tomb and at his Ascension, the attention of the disciples was fixed on what Jesus had already done and on the places where they had known him. The task of the angels, God’s messengers, was to move the attention of the disciples from the past on to what they must now do in the present. Only when this was accomplished, could they continue the ministry that Jesus had begun, but now in places the historical Jesus had never been.

The disciples easily could have held on to the places in which Jesus had done this or that, or to objects Jesus had touched or held. In other words, they could have remained in Galilee. To be faithful to the ministry to which Jesus had called them, they had to give up the “souvenirs” which might have held them to the past and its demands, and move towards Jerusalem. If they had held on to the past, they would have missed new opportunities for lively mission and ministry.

Think of the ways in your life in which you may be holding on to the souvenirs of the past. Would you be willing, if God called you in a similar manner to move from the safety of Galilee to the risky and uncertain Jerusalem, knowing that there you would be empowered and your life renewed and restored by God’s holy and life-giving spirit? God’s promise to us is that we can let go of everything from the past that hinders us and that God will renew, reform, and restore us by the power of the Holy Spirit. What would it take for you to step forward in faith?