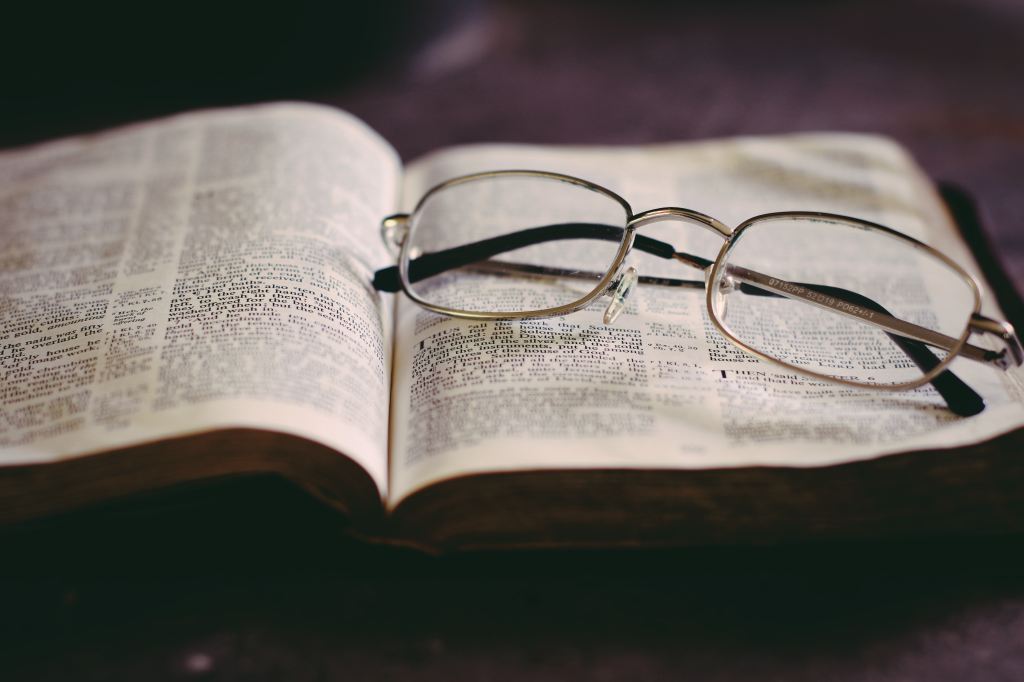

In Mt. 25: 1-13, we find Jesus’ parable of the wise and foolish bridesmaids which concerns their preparedness at the parousia, the return of the Jesus the bridegroom at his second coming: five were ready when the bridegroom returned at an unannounced time, but five were not. The five who were prepared with oil in their lamps could not share what they had because, readiness is not something you can share. It is something you have to cultivate within..

This story of the bridesmaids allows me to do something I rarely do in the pulpit and that is to connect what I have been writing on as an academic with what I preach. In the past ten years I have published numerous articles and chapters on the work of Giorgio Agamben. (You can find the bibliographic information on the page of this blog listing my academic publications.)

Giorgio Agamben is one of the most prominent continental philosophers alive today. He is a former student of Martin Heidegger, and even though he could be described as an atheist and somewhat of a philosophical anarchist, his work is based primarily on religious and theological texts, including a commentary on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans and a book on St. Francis and monastic rules. I became interested in him because he was the Italian editor of the writings of Walter Benjamin on whom I wrote one half of my doctoral dissertation and because of his use of theological texts in his non-religious philosophy. Agamben, I might add, is not easy to read or to understand.

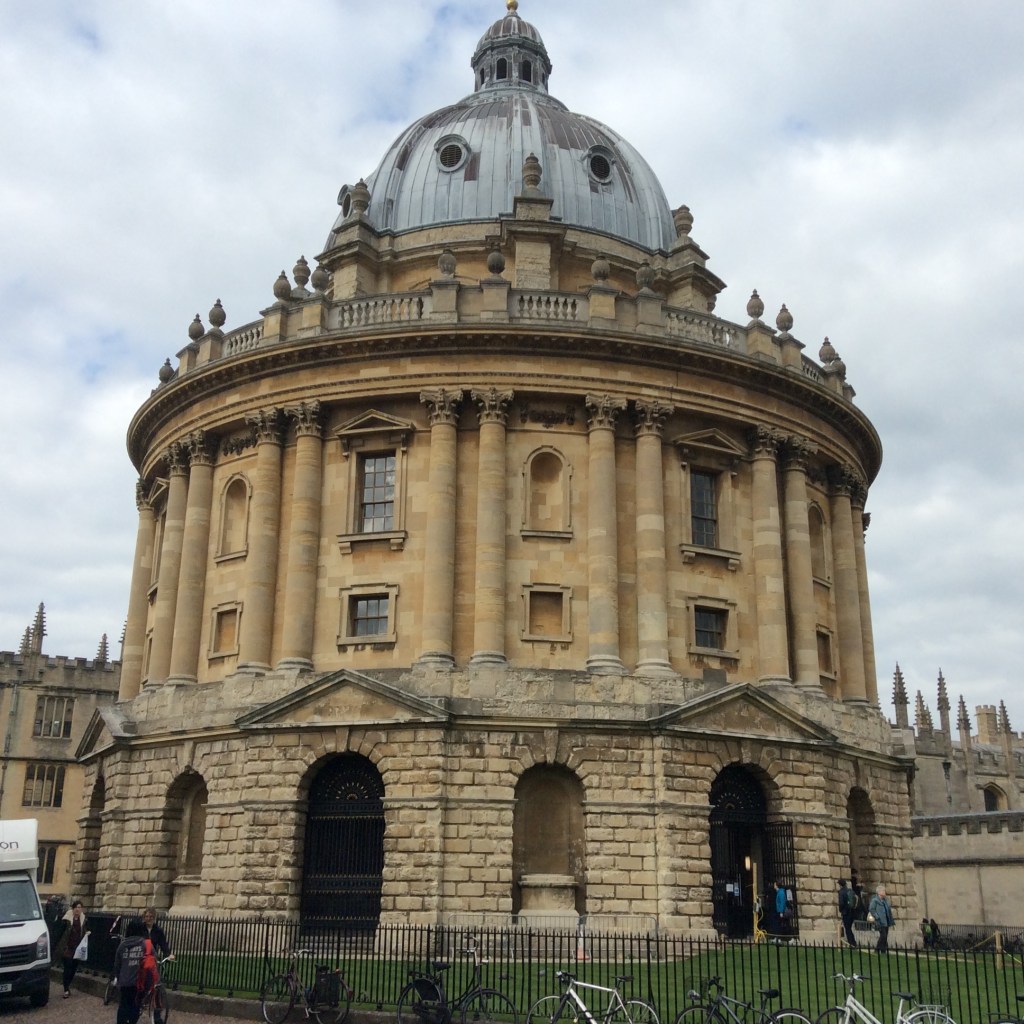

In March 2009, Agamben was invited to Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris to give a lecture on his critique from his own philosophical perspective on the Roman Catholic Church. This address was subsequently published as The Church and the Kingdom. [1]

The earliest Christians, as is evident in the parable of the wise and the foolish bridesmaids in the Gospel of Matthew and in St. Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians expected that the crucified and resurrected Jesus might return at any moment. St. Paul told Christians in his early writings that they should make no drastic changes to their life because Jesus was going to return any moment. If they were not married, for example, they should hold off marrying because the Lord might return at any moment. The present form of the world, he said more or less, is passing away, so don’t get too attached to it. (1 Cor. 7:31).

In his address in Paris, Agamben observed that “the Christian church has ceased…to sojourn as a foreigner,” and begun to dwell in the world and “live as a citizen in the world and thus function like any other worldly institution.” As the years went on and Christ did not return, the church began to settle in the world and put down roots. It ceased to sojourn and began to dwell. This for Agamben is the root of his critique of the church. [2]

The difference between sojourning and dwelling is something like the difference between being nomadic and settling down and building permanent dwellings. When you begin to dwell you get tied down to your own possessions and lose the ability to move quickly when needed, or adapt to changes.

St. Paul proclaimed freedom from the law. He urged Christians to live in the Holy Spirit in joyous freedom from the law. When the church began to dwell in the world, it became like other worldly institutions and set up legal structures that effectively replaced the law from which they, in Christ, had been freed. Agamben investigates St. Francis and other monastic rules, which in Latin are called regula (from which we derive our English word regular) to see if he could provide an alternative today for law (Latin, lex), investigating how one might free oneself from servitude to law in all of its contemporary manifestations.

To address this, Agamben does something quite interesting. He turns to St. Francis of Assisi and the first Franciscans. Francis wanted to live his life according to one rule only, namely that he live as Jesus Christ lived. He, therefore, renounced all his possessions so that he would be free from them and thus able to respond to Jesus in every area of his life. Francis became a kind of nomad. He gave up the idolatry of his possessions and found freedom. In his poverty he found exhilaration and joy. In subsequent centuries after Francis, Franciscans tried to figure out how, if they were going to live a life of perfect poverty, they could “use” things without owning them. Agamben turns to these texts and discussions to glean what he can for his own philosophical and political work.[3]

Returning to the story of the bridesmaids, five of them were ready but five were not. Why were the other five not ready? The story doesn’t tell us. Without reading too much into the parable we could surmise that they had been busy. They put off getting oil because they had other things to do, which at the time seemed more important.

Could it be that they had ceased to sojourn, and begun to dwell? They had become so attached to the things of this world and to the care of them, that they were not ready and prepared when the bridegroom (who in this story is clearly the person of Jesus Christ) returned. They had been claimed by what they owned and not by the person who owned them, Jesus Christ. This idolatry of things and possessions prevented them from the freedom to follow Jesus wherever he led.

The parable of the wise and foolish bridesmaids ends with these words, “Keep awake therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour.” We know neither the day nor the hour of the Lord’s return. So, prepare yourselves. Begin by examining the things that hold you back—that tie you down—that enslave you— that keep you from responding to Jesus and his call to you. Can you begin to use things without owning them? Can you begin let go of the things that hold you back that keep you tied down? You can only be prepared for yourself. You cannot be prepared for someone else. “Keep awake therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour when the bridegroom will return.” The question for you is, “when he does return, will you be ready?”

[1]Agamben, Giorgio, Leland De la Durantaye, and Alice Attie. The Church and the Kingdom. (London ; New York: Seagull Books, 2012).

[2] “…The Christian church has ceased to paroikein, to sojourn as a foreigner, so as to begin to katoiken, to live as a citizen and thus function like any other worldly institution. See Agamben, The Church and the Kingdom, p. 4.

[3] Agamben, The Highest Poverty. Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life. (Stanford, California: Stanford UP, 2013.